The Promise and Peril of the Photo Ark

There is something both amazing and deeply disturbing about Joel Sartore’s Photo Ark. The premise is simple. Document as many captive species as possible with stunning visual imagery and use these images to create awareness and mobilize public support for protecting biodiversity globally. The fight to protect global biodiversity is a laudable goal and one we should all support.

White-Headed Brown Lemurs. (Credit: Joel Sartore)

What worries me is that in the process of trying to capture the public imagination with these other than human images, we run the risk of turning them into a spectacle of pity for capitalist consumption, thereby missing the entire point of biodiversity conservation, namely the actual conservation of species. A second point, which is also worrisome to me, is that most of these images are the product of the institutional enclosure movement–better known as zoos. Many people have made persuasive arguments about the problematic role of zoos and similar other than human captivity centers as inherently cruel and ultimately harmful to the spirit of wild beings. Even National Geographic, for which Sartore worked for many years as a photographer, recognizes as much when it describes a zoo as “a place where animals live in captivity and are put on display for people to view” (my emphasis).

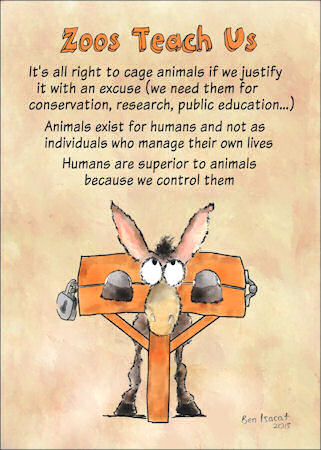

What Zoos Teach Us. (Credit: Ben Isacat)

While it is true that there are good zoos and bad zoos in terms of how much attention they give to recreating something vaguely like a natural habitat, the basic point remains that once you enter a zoo, all remnants of the wild living vanish. You now live in a cage with fixed feeding schedules and year-round crowds gawking at you day in and day out–a far cry from living in the wild. While some people have argued that it is better to try and save critically endangered species in zoos than let them simply go extinct in the wild, I don’t find this to be a convincing argument. For starters, it denies that something critical is lost when we move a being from a state of absolute freedom to captivity. I think we do.

Furthermore, the solution to stopping extinction is habitat protection combined with restrictions on human encroachment, especially industrial agriculture and urban sprawl, not captivity. So the thrust of the argument in defense of zoo conservation misses the larger political critique of habitat destruction which is an essential part of arguments in favor of biodiversity conservation. As long as we continue to see zoos as some kind of biological conservation ark, we are missing the basic argument from critical conservationists. The intrinsic value of all life is what is at stake for other than human beings, and the basic right to live a life free of exploitation. For zoo advocates, this kind of claim takes the ontological politics of species too far for their comfort. But even if we take the “zoo ark” idea at face value as a gesture of good faith, the fact remains that it has failed, as Jon Cohen argues in an excellent piece on Zoo Futures in Conservation Magazine.

“The problem that zoos have when it comes to rescuing endangered species and promoting conservation is that they have been able to do only “just little things” themselves. Many of the larger zoos have bought into a concept that they must work together to provide a Noah’s Ark for threatened and endangered species until humans come to their senses and stop their wanton destruction of the environment. Some zoo visionaries even tout the promise of cloning endangered or extinct species from DNA retrieved from animal samples in frozen zoos, like the one maintained by the Institute for Conservation Research. But the numbers don’t lie: as [UCSD conservation geneticist David] Woodruff and several other researchers have documented, zoos—despite tremendous scientific advances in breeding and caring for captive animals—have failed to maintain their own collections.”

But the fact remains that zoos are here for now, whether we like them or not, and so we have to deal with that reality as part of the larger matrix of conservation politics. But there are other encouraging trends beside thinking about zoos as conservation arks. For example, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a leading international body focused on species conservation, is holding their World Conservation Congress in September of 2016 in Hawai’i, with the theme of Planet at the Crossroads. “The world is facing a rapidly closing window – our planet is at the crossroads,” argues IUCN Director General Inger Andersen. “The path we choose today will define nature’s ability to support us as a species during our lifetimes and for generations to come.” In going through the program materials for the IUCN Congress, it is clear that the stakes for conservation advocates is quite high, as the following excerpts from the World Congress theme brief highlights.

“There is a real sense of urgency in this call to action, as many believe that current trends are not sustainable and that there is a closing window of opportunity to effect meaningful change in Humanity’s trajectory. Our future will be decided by the choices we make now.

IUCN believes that a steady increase in global wellbeing can only be achieved through an enhanced understanding of the planet’s complex life support systems and the predominant global trends currently acting upon them–urbanisation, economic growth, burgeoning consumption, disappearing biodiversity, wealth inequality, climate change, population growth, and so on.Time is running out for humanity to find ways of progressing that safeguard and reinforce the natural world that sustains us. In one form or another, Nature will most likely go on, so the relevant question is: to what extent will healthy, prosperous and secure societies continue to be a part of the story, and how much of the greater community of life will persist?

The current debate is framed by two competing narratives. One is a pessimistic view of our future which claims that it is already too late to avoid catastrophe, and therefore we must now focus on survival and recovery. This leaves people in despair. The other is a stubborn optimism arguing that Humanity has faced and overcome many great challenges in the past and will continue to do so. This risks indifference and denial.

There is, however, an emerging viable alternative – one that embraces the reality that we live in a world of complex, interdependent systems and acknowledges that changes to these systems can either enhance resilience or result in greater instability and uncertainty. This alternative future has been given expression by the international community through various declarations, including The World Charter for Nature, Agenda 21, The Earth Charter, and the U.N. General Assembly resolutions on Harmony with Nature. Collectively, they point to the need for profound transformations in our patterns of production and consumption, and recognition that every form of life has value regardless of its worth to human beings.

The alternative approach stresses that nature conservation and human progress are not mutually exclusive. Facing tremendous forces of transformation such as climate change and dramatic socioeconomic inequality across the world, there are credible and accessible political, economic, cultural and technological choices that can promote general welfare in ways that support and even enhance our planet’s natural assets.

To inform these choices, IUCN has been aligning conservation efforts all over the world around three solid lines of work: valuing and conserving Nature’s diversity, advancing effective and equitable governance of the use of Nature, and deploying Nature-based solutions to climate, food and development challenges. The approach that is emerging from our collective efforts demonstrates that Nature is not an obstacle to human aspirations, but rather an essential partner, offering valuable contributions towards all our endeavours.”

Since some of my academic research and work in recent years has been focusing on the politics of the rights of nature, it is particularly interesting to see the IUCN beginning to also invoke this same language, especially the Earth Charter and the UN GA’s resolutions on Harmony with Nature. Both mark important international efforts to develop a new politics of the Earth, or what I have been writing about as the new social movement of Earthbound people. But since this is a large and separate topic, I don’t want to delve into that in this post. For those interested, I have discussed some of this here.

Going back to Sartore’s conservation photos, it was purely by chance that I stumbled upon the original NBC story featuring the Photo Ark (Joel Sartore’s Photo Ark Pictures). I had been going over the day’s news headlines–mostly highlights of people dying, bickering over politics, and fretting over the general chaotic state of the world. In other words, more of the usual fare. It was the bright colors of a Sartore photo that caught my attention amidst the news clutter and brought me to the story on his photos and the Ark. For anyone interested in the Photo Ark project itself, you can visit Joel Sartore’s website to learn more about why he started doing this. For the more social media inclined, you can also follow him @joelsartore. Despite my reservations about the coffee table conservation implications of such a project, it is undeniable that he is an amazing photographer.

But what most intrigued me when I saw these images was the story behind the story, so to speak. How did he get such stark black and white images? Fortunately there is a nice little piece done a few years ago talking with Joel about this project, and some shots of him actually doing the work of making the Photo Ark. This was what I was most interested in, since the sharp black and white backgrounds are part of what makes the pictures so visually rich. That and the stunning natural colors of these diverse other than human beings, which let’s face it, put any 5th Avenue fashion designer to shame in a hot second. Wow, nature is so fricking amazing! Here’s the short video I mentioned showing a bit of the behind the scenes with Sartore.

I have no idea how much of an impact these images have had on people, much less contributing to biodiversity conservation, so it is hard to know where the line between effective political engagement and coffee table consumerism falls on something like this. If you listen to some of Sartore’s talks, you’ll hear him describe the impact of one particular photo, this one, which likely played a role in shifting state policies in northern Australia around koala protection. So I don’t want to rule out the possible political impacts of a project like this. I’ll be the first to admit that I love visually stunning, large-format photo books that are heavy with photos of the land and its diverse inhabitants. If they have some kind of conservation message alongside, all the better. But I also understand the importance of getting out into the world and fighting to save it, not just enjoy it frozen forever in still life. And that is really my biggest fear, or worry, about these kind of endangered animal documentation projects. Rather than serving as a tool to help preserve biodiversity into the future, they become a record of what we lost in the past. All I can hope is that Sartore’s Photo Ark moves people to do more than just enjoy the extinction spectacle.

Until next time…if you love something, don’t be afraid to fight for it.

###