Hello, and welcome to the Anthropocene section of my blog.

Are we really in a new geologic epoch, the “Age of Humans,” where people have become the master the planet, or is this just the latest anthropocentric fad dressed up in a new set of clothing? What does this idea have to do with claims about “post-natural” or “post-environmental” politics and the “end of nature”? Ultimately that answers depends a lot on how you understand these terms and your own political orientation. But before all that, here’s some basics on the Anthropocene. I try to keep this page up to date, but with the explosion of research since 2000, it’s basically impossible to do this full time, so apologies in advance for outdated references, since I have not updated this since 2020.

If you’re wondering what this page is all about, you can read more here.

Background

The Anthropocene is the name for a new geologic epoch which was originally proposed by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in the IGBP’s Global Change newsletter in 2000 in an article simply called “The Anthropocene.” In this article Crutzen and Stoermer proposed that due to a vast and growing impacts of humans to the planet we have become a force on par with geologic change and forces, and this fact warranted the creation of a new geologic epoch to signal this new relation. They suggested that a good starting point was around 1800, the point in time when our relationship with Carbon began to increase significantly. Here’s an excerpt from their piece about just how big an impact humans are now having on the planet, which is preceded by a long list of human impacts to the land, air, water, soil, atmosphere, communities and ecosystems:

Considering these and many other major and still growing impacts of human activities on earth and atmosphere, and at all, including global, scales, it seems to us more than appropriate to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology by proposing to use the term “anthropocene” for the current geological epoch…To assign a more specific date to the onset of the “anthropocene” seems somewhat arbitrary, but we propose the latter part of the 18th century…because, during the past two centuries, the global effects of human activities have become clearly noticeable. This is the period when data retrieved from glacial ice cores show the beginning of a growth in the atmospheric concentrations of several “greenhouse gases”, in particular CO2 and CH4. Such a starting date also coincides with James Watt´s invention of the steam engine in 1784…[and]…biotic assemblages in most lakes began to show large changes.

So in short, we should call an end to the Holocene, our current geologic epoch, and herald in the emergence of this new epoch, the Anthropocene. You can get some of more background on this topic from a 2008 GSA article titled “Are We Now Living in the Anthropocene?” As of early 2016 the Anthropocene Working Group within the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), the folks who make the final determination on geologic dating, suggested there is a good case for the Anthropocene. In their Science article “The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene,” they suggest that the mid 1950s, sometime around the testing of the first nuclear bomb and the rise of stuff like plastic, would be a likely starting point. Here’s an excerpt from this piece.

So in short, we should call an end to the Holocene, our current geologic epoch, and herald in the emergence of this new epoch, the Anthropocene. You can get some of more background on this topic from a 2008 GSA article titled “Are We Now Living in the Anthropocene?” As of early 2016 the Anthropocene Working Group within the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), the folks who make the final determination on geologic dating, suggested there is a good case for the Anthropocene. In their Science article “The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene,” they suggest that the mid 1950s, sometime around the testing of the first nuclear bomb and the rise of stuff like plastic, would be a likely starting point. Here’s an excerpt from this piece.

Recent anthropogenic deposits contain new minerals and rock types, reflecting rapid global dissemination of novel materials including elemental aluminum, concrete, and plastics that form abundant, rapidly evolving “technofossils.” Fossil fuel combustion has disseminated black carbon, inorganic ash spheres, and spherical carbonaceous particles worldwide, with a near-synchronous global increase around 1950. Anthropogenic sedimentary fluxes have intensified, including enhanced erosion caused by deforestation and road construction. Widespread sediment retention behind dams has amplified delta subsidence.

Geochemical signatures include elevated levels of polyaromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, and pesticide residues, as well as increased 207/206Pb ratios from leaded gasoline, starting between ~1945 and 1950. Soil nitrogen and phosphorus inventories have doubled in the past century because of increased fertilizer use, generating widespread signatures in lake strata and nitrate levels in Greenland ice that are higher than at any time during the previous 100,000 years.

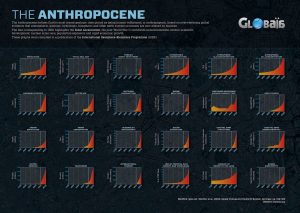

Originally the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) had put together a great beginner resource on the science behind the Anthropocene, which you can check out at www.anthropocene.info. With the closing of the IGBP project at the end of 2015, a lot of their work has now moved to Future Earth, which is one of the new homes for a lot of the current Earth Systems science and Earth Systems Governance work they were supporting. Some of that same content can be found on the Globaïa site here. There are also now a handful of journals dedicated to the Anthropocene, which you can find below:

- Anthropocene (Elsevier)

- The Anthropocene Review (Sage)

- Anthropocene Magazine (Future Earth)

- Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene (U. of California Press)

- Anthropocene Coasts (Canadian Science Publishing)

This is the animation done by Globaïa for the short film ‘Welcome to the Anthropocene’ commissioned for the Planet Under Pressure conference. The film charts the growth of humanity into a global force on an equivalent scale to major geological processes. The film is part of the world’s first educational web portal on the Anthropocene.

Some influential early popular coverage of this issue can be found in an Economist piece: The Anthropocene: A man-made world and a Nature article titled Anthropocene: The Human Age.

Erle Ellis, one of the early Anthropocene proponents, recently wrote ‘Anthropocene: A Very Short Intro,’ which is a good starting point for those interested in the topic. It has its problems, but does a good job of covering the main issues and evolution of the idea since 2000. Plus it’s fairly up to date, which is also helpful.

Erle Ellis, one of the early Anthropocene proponents, recently wrote ‘Anthropocene: A Very Short Intro,’ which is a good starting point for those interested in the topic. It has its problems, but does a good job of covering the main issues and evolution of the idea since 2000. Plus it’s fairly up to date, which is also helpful.

As of 2019 the Anthropocene Working Group in the ICS has not had much luck getting their pet epoch adopted. In fact, just the opposite happened. A rival group of geologists were able to have the Holocene Epoch, which we are currently living in, broken into 3 smaller periods: the Meghalayan, the Northgrippian, and the Greenlandian. You can read some of the context and substance of this academic feud here and also here. The later of these articles, from the Atlantic, has by far my favorite take away from these debates so far:

“What the fuck is the Meghalayan?” asked Ben van der Pluijm, a geologist.

Whatever the Meghalayan is, we live in it now.

Earlier this week, the International Commission on Stratigraphy announced that the current stretch of geological time, the Holocene Epoch, would be split into three subdivisions.

So for now, it seems the fate of the Anthropocene remains uncertain, at least as a new formal geologic designation. You can follow the latest developments in the dating debates from the ICS Anthropocene Working Group here.

There was also a movie made recently which won some awards, called Anthropocene: The Human Epoch. Below is a copy of the trailer for the film.

What is less uncertain, however, is that the idea of the Anthropocene is not going away, and folks in the humanities and social scientists have taken this idea up with gusts; to say nothing of its pop culture fandom, which grows in size every year.

My own work seeks to develop what I refer to as a Critical Anthropocene, one which neither accepts the ‘End of Nature’ nor the ‘Age of Humans’ arguments, but instead calls for thinking about the Anthropocene as a political concept which signals the necessity of a ‘New Human’, in other words, a remaking of what it means to be human, more in line with living in a multi-species world not of our own making.

You can find all of my posts to date which focus on some aspect of the Anthropocene here.

About this page

I write about social movements in the Anthropocene, especially issues of land rights and the intersections of social and environmental justice and Indigenous rights. This page is a temporary starting point for some of my engagements with the Anthropocene. I had planned to build a fully dedicated Anthropocene research site–but the contingencies of life put that project on hold.