Political Science and the Problem of Democracy

This post was sparked by a recent article in Vox reporting on a conference at Yale titled How Do Democracies Fall Apart (And Could it Happen Here)?

The conference was organized by Bright Line Watch, and the focus was a discussion with a group of political scientists about the state of democratic politics in the US. The article began with this seemingly innocuous headline: “20 of America’s top political scientists gathered to discuss our democracy. They’re scared.”

Given the state of political discourse–and actual activity–at the moment, this was not an entirely unsurprising conclusion. But I was curious what exactly had got them scared. After reading the piece, I’m skeptical this was in fact a gathering of our “top” American political scientists. Or if it is, it’s a sad commentary on the state of the discipline. More on that in a moment.

Here’s the opening lines of the article, to give you a feel for the tone of the piece:

Is American democracy in decline? Should we be worried?

On October 6, some of America’s top political scientists gathered at Yale University to answer these questions. And nearly everyone agreed: American democracy is eroding on multiple fronts — socially, culturally, and economically.

The scholars pointed to breakdowns in social cohesion (meaning citizens are more fragmented than ever), the rise of tribalism, the erosion of democratic norms such as a commitment to rule of law, and a loss of faith in the electoral and economic systems as clear signs of democratic erosion…there was a sense that the alarm bells are ringing.

What should we make of claims about the alarm bells of democracy sounding?

It’s true that the state of political discourse and cooperation at the moment seems terribly partisan and anemic, but does this warrant such dire forecasts for the future of democracy?

The Importance of History

Because the classes I’m teaching this semester are tracing the emergence and rise of democratic theories and the formation and consolidation of the US Republic, these opening claims set off my skepticism detector. A declining commitment to the rule of law and the rise of partisan “tribalism” are quite old phenomenon, as any serious student of US history knows. In fact, these are some of the very issues my political science students have been learning about the past several weeks in class.

If that’s the case, why are a bunch of supposedly top American politics scholars describing these as new threats to democracy?

One answer might be that, in fact, many of them aren’t actually scholars of American politics, or at least not US political history. If they were, two obvious counter-examples should have come to mind when someone claimed the weakening rule of law or political tribalism were new forces which threatened to tear the Republic asunder.

Kurz and Allison – Battle of Franklin, November 30, 1864

Counter-Example 1: American Civil War

Anyone claiming the US is witnessing a new and profound crisis in our commitment to the rule of law, one that hearkens the end of democracy, should spend a few hours brushing up on Civil War history. You would be hard-pressed to find a more glaring example of the “erosion of democratic norms such as a commitment to rule of law” than eleven states seceding from the Union and starting a civil war to protect the aristocratic slave society of the South.

To understand why such historical amnesia is dangerous, consider the following discussion from professor Timur Kuran and what he called the “intolerant communities” problem:

Timur Kuran, a professor of economics and politics at Duke University, argued that the real danger we face isn’t that we no longer trust the government but that we no longer trust each other. Kuran calls it the problem of “intolerant communities,” and he says there are two such communities in America today: “identitarian” activists concerned with issues like racial/gender equality, and the “nativist” coalition, people suspicious of immigration and cultural change. Each of these communities defines itself in terms of its opposition to the other. They live in different worlds, desire different things, and share almost nothing in common. There is no real basis for agreement and thus no reason to communicate. The practical consequence of this is a politics marred by tribalism. Worse, because the fault lines run so deep, every political contest becomes an intractable existential drama, with each side convinced the other is not just wrong but a mortal enemy.

Any political analysis that reduces a diverse and complex country of 326 million people into two categories is already suspect in my mind, but for the sake of argument let’s play out the idea.

Debates about the supposed harms of identity politics and political correctness have been circulating since at least the 1970s, a product of the conservative backlash against sixties cultural politics and the rise of freedom struggles by historically marginalized peoples. The language of “identitarian” politics simply recycles these old conservative talking points. These supposedly intractable differences have not stopped the US from passing many small but important social reforms in recent decades, hardline conservative opposition notwithstanding. Yes, there are definitely sociocultural divisions within the US, but not a simple “identitarian vs nativist” binary as Kuran would have us believe. Rather, it seems that the idea of “intolerant” communities is a convenient narrative meant to bolster conservative criticisms of social change aimed at addressing historical injustices, rather than revealing any fundamental political truth about the US polity.

Not surprisingly, Kuran’s ideological bedfellows can be found in places such as Cato Unbound, which is affiliated with the conservative Cato Institute think tank, a long-time critic of anything social justice related.

Similar to Trump’s comments about white power rallies in Charlottesville involving violence “on many side,” Kuran’s claim that demands for racial justice and gender equity are somehow politically equivalent to nativist xenophobia and racism is deeply flawed and needs to be challenged. Demands for social justice are seek precisely to challenges such forms of intolerance.

If we need a reminder of what intolerance looks like (if recent events in Charlottesville and Gainesville aren’t enough), we should recall the infamous “Cornerstone Speech” by Alexander Stephens, who was then Vice President of the newly formed Confederate States of America. Delivered in Savannah, Georgia on March 21, 1861, less than a month before the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, his speech epitomizes racial intolerance and hatred:

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth. This truth has been slow in the process of its development, like all other truths in the various departments of science. It has been so even amongst us. Many who hear me, perhaps, can recollect well, that this truth was not generally admitted, even within their day. The errors of the past generation still clung to many as late as twenty years ago. Those at the North, who still cling to these errors, with a zeal above knowledge, we justly denominate fanatics. All fanaticism springs from an aberration of the mind from a defect in reasoning. It is a species of insanity. One of the most striking characteristics of insanity, in many instances, is forming correct conclusions from fancied or erroneous premises; so with the anti-slavery fanatics…They [Northern Abolitionists] were attempting to make things equal which the Creator had made unequal.

It’s hard to imaging a more clear-cut case of intolerance than white supremacy justified as a divine social order.

Demands for racial and gender justice of the kind Kuran associates with leftist identity politics are diametrically opposed to this kind of intolerance. On that point there is can be no debate.

Counter-Example 2: American Nations

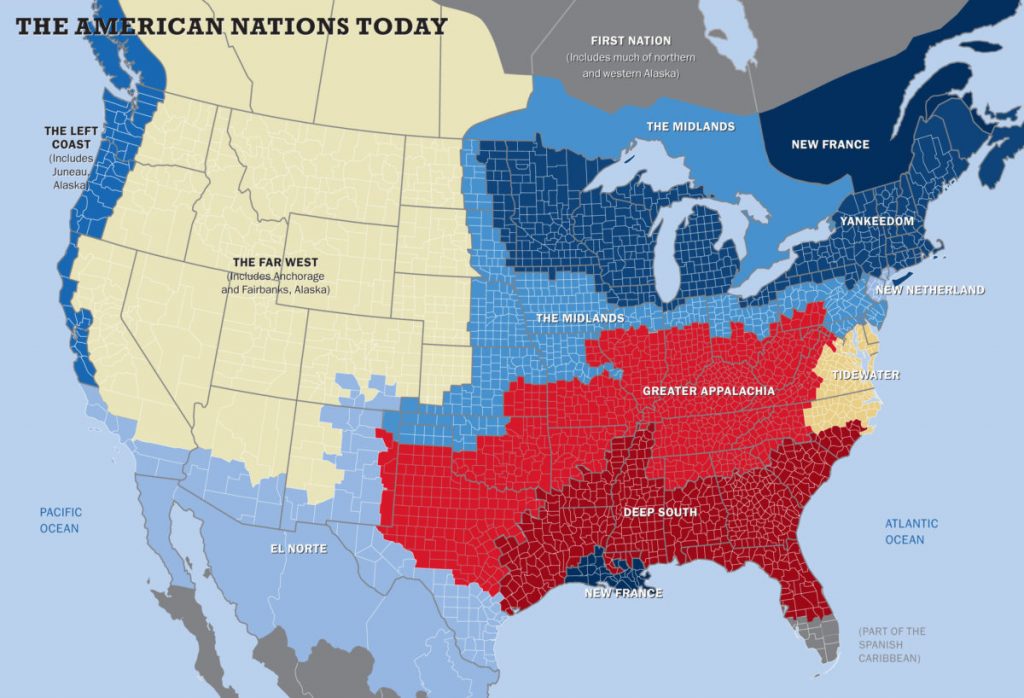

One of the texts I’m using in class is Colin Woodard’s American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. Woodard’s book offers an excellent historical examination of how the early US Republic came to be, and the many diverse cultural groups that gave birth to the fledgling nation, starting with the initial waves of Spanish, French, Dutch, English, German, Irish, and Scottish immigrants. In addition, there are the thousands of distinct Native communities who were already inhabiting the Americas. All of these groups left a distinct imprint on the character of the US, and while some may be more evident in certain areas, no one is dominant across the entire country.

For those unfamiliar with Woodard’s argument, his basic premise is that eleven distinct nations settled the US and their left their imprints on the American character, evidence of which is still visible today. It is precisely these past influences that help explain–at least in part–many of the peculiar aspects of US regional politics and culture.

This map shows the American Nations that Woodard discusses in his book, with each of the distinct colors representing one of the eleven nations. (More details on his website here.)

For anyone familiar with his book, or the larger historical processes Woodard trace–setting aside for a moment the question of how many “nations” we could describe and where the boundaries between them are drawn–claims that the US was at any point not a nation of tribes (politically, ethnically, culturally) struggling with each other for political hegemony ring hollow. The North American continent has always been a land of tribal nations, from the first Indigenous peoples to later waves of European settlers and immigrants that began to arrive in growing numbers starting in the 17th century.

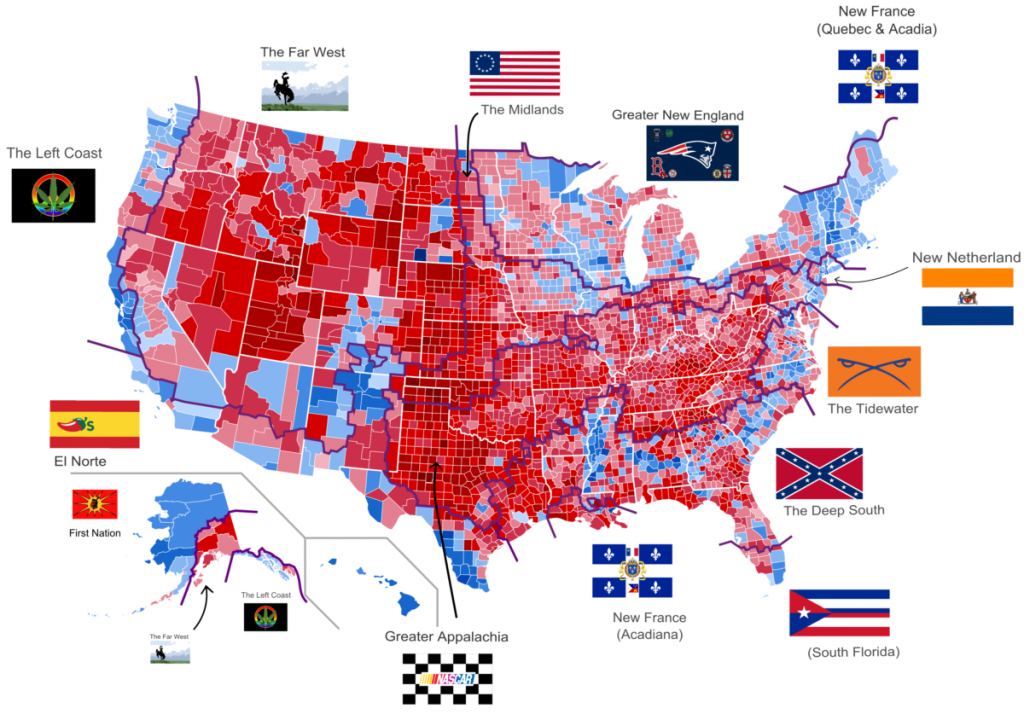

I’m a map fan, and JayMan’s blog has a plethora of maps visualizing the American Nation thesis. This one from 2012 gives an idea of how these distinct “nations” continue to shape US politics. As he notes, the following map “details the straight voting percentage, outlining the red [Rep.] and blue [Dem.] counties. The blueness of Greater New England, the Left Coast, and the Midlands compared to the rest of the country becomes clear.” For the map geeks among us, also take a look at these maps and these maps for more examples of mapping these cultural patterns.

As Woodard and others argue, and as maps like this one help to visualize, there is nothing new about a tribal America.

But it seems these are not the only potential problems that were unresolved by these top scholars debating the future of democracy. One other issue stood out and is worth addressing.

Defining Democracy

Before we start declaring democracy dead or imperiled, it would be helpful to know what exactly it is we understand when we refer to “democracy” as a concept. Unfortunately, there is no indication in the article if this questions was ever addressed at the Yale gathering. If it was, it was not highlighted as important enough to merit even a passing reference in the author’s memory.

This is problematic, given there is no single, agreed-upon definition within political science as to what “democracy” means. Is it an ideal, a system of government, or a process for political decision-making? This is a basic issue that the Vox article failed to even mention. It’s hard to tell if this is a shortcoming of the author’s own understandings of democracy, or of the political scientists gathered at Yale. Either way, it is a fundamental oversight that makes any critical discussions about democracy hard to take seriously.

In my class we have been discussing the many theories of democracy and the important differences between them. Here are just a few “democratic” theories that incorporate some idea of democracy into them:

- Pure Democracy – classical Athenian politics (Plato, Aristotle)

- Republican Democracy (Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Rousseau)

- Bourgeois & Proletarian Democracy (Lenin)

- Modern Mass Democracy (Weber)

- Participatory Democracy (Pateman, Dewey)

- Radical Democracy (Hardt & Negri, Mouffe, Ranciere)

There is more one could say about this article and the apparent outcome of their meeting, but that is best left for a future post.

All this is to say that when reading articles claiming that democracy is at risk of collapsing, we should pay heed, but also take such claims with a healthy dose of salt.

Or at least that’s what my years of political science training has taught me.

You can find the full article here on Vox.