Diane Ackerman Sadly Peddling “Good Anthropocene” Myth

These days my first reaction is to prepare to cringe whenever I see a headline with the Anthropocene in it, which is ironic given that this is also my dissertation topic. How about that! More seriously, what I am always hesitant about is seeing the growing meme of the “good Anthropocene” which, now even Diane Ackerman is writing about. This is really a shame, as I enjoyed her earlier work A Natural History of the Senses when I read it. But it seems that Ackerman, like so many other well-meaning but ill-informed liberals, has bought into the myth of the “good Anthropocene” and the dream of technological salvation. Since I have several news alerts setup to track this topic, I always see what is new and trending on the Anthropocene, and I think the critical review in the Toronto Star by Kate Allen is spot on. Here’s an excerpt from her review of Ackerman’s new book, called The Human Age:

How would you feel if you killed your mother? Pretty bad, probably.

Humanity — the whole whack of us — is suffering from wide-scale psychological trauma of a similar kind, Diane Ackerman believes.

“I think maybe we’re walking around with a sort of mass depression about what we are doing. We refer to the planet as female: Mother Earth. Mother Nature. Okay, now we’re being told that we are killing our mother, our mother is going to die, and it is our fault.”

Ackerman, the best-selling author, poet and naturalist, has just the fix: her new book The Human Age: The World Shaped By Us, a lyrically-wrought romp through some of the innovative solutions, adaptations and modifications our species has created for our broken planet and our increasingly hot and uncomfortable place in it.

If you buy Ackerman’s diagnosis of collective malaise, this book is a balm. From green roofs to aquaculture, the spirit of The Human Age is clear: if we embrace our capacity for creativity, we might still be okay.

“We are going in the right direction. We know what to do. We just have to get motivated. And there is absolutely no way to do that if all that we are confronted with is doom and gloom,” Ackerman says.

But there is one critical question Ackerman fails to answer, and I am not the first to ask it: Who is “we”?

And sadly, it is this total inability to comprehend the question of the “we” that is partly at the root of both liberal and conservative climate denialism.

It is precisely the same logic that lets arrogant faux-green liberals like Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger (of the Breakthrough Institute) feel justified in criticize the environmental justice movement for not being effective and focusing too much on–egad–stuff like neighborhood pollution and toxins, and not the “real” big issues like investment in green tech, all the while glibly cooing over chilled wine and talking about their grand future vision of a restored American Liberalism and our supposed “post-scarcity” society. When UTNE Reader asked Michael Shellenber about his criticisms, and the cool response he received from enviro justice circles to the arguments he and Nordhaus made in their book, here was his response:

What started out as an effort to make environmentalism more expansive ended up making it even more narrow. The challenges facing poor communities of color go way beyond air and water pollution. They have far less access to healthy food; they have less health care security, less child care security. They’ve got crappier schools. There’s more stress and disempowerment. So to create a politics that’s centrally focused on toxic contamination or diesel bus pollution is reductive and speaks to a set of things that are very low priorities in comparison to the much bigger factors driving health and life outcomes.

Of course, it’s easy to tell a community in the South Bronx that increased asthma linked to diesel pollution from the MTA bus terminal in their neighborhood is a small issue while breathing fresh ocean air in a Berkeley cafe and sipping local wines–its quite another to actually know what you are talking about from a lived daily experience.

As Clive Hamilton rightly pointed out in his critique of Andrew Revkin’s awful “good Anthropocene” talk given at the AESS conference I attended here in NYC earlier this year, as well as the politics of possibility peddled by Shellenberger and his ilk (to which I guess we now have to add Ackerman):

The answer, they say, is not to change course but to more tightly “embrace human power, technology and the larger process of modernization”. The argument absolves us all of the need to change our ways, which is music to the ears of political conservatives [and I would add liberals]. The Anthropocene is system-compatible. This technoutopian vision depends on a belief that, with the advent of the new geologic epoch, nothing essential has changed. This reimagined Anthropocene rests on a seamless transition from the fact that humans have always modified their environments to a defense of a postmodern “cyber nature” under human supervision, as if there is no qualitative difference between fire-stick farming and spraying sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere to regulate Earth’s temperature

In case you missed that, you can watch Revkin’s talk here on online.

Sadly Ackerman seems to also have been seduced by the siren’s song of the Anthropocene, at least on Allen’s reading of the politics of Ackerman in her latest book. “With Human Age, Ackerman has firmly installed herself as the poet laureate of the [Anthropocene] optimist camp.” Of course, optimism is relative, and much like hope, is full of let downs when it comes face to face with reality. This is doubly true of climate reality.

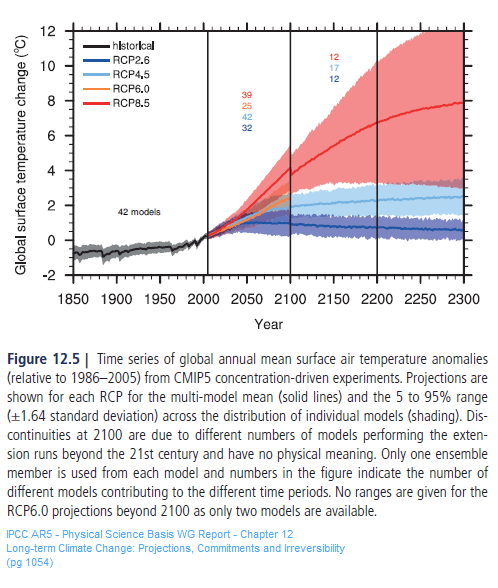

Speaking of climate reality, it now looks like the latest debate in scientific climate circles is no longer over how to meet the 2-degree C temperate threshold that nations agreed to through the various IPCC negotiations, but rather if we should stop talking about 2-degree C and instead talk about a 3-degree C limit. That’s because there is less than a snowball’s chance in hell that the world will stay under 2-degree C, and the scientists all know it. The rebuff from India to attend the recent UN Climate Summit, and China sending a party member with deep ties to the energy and coal industry, are just a few of the many example of this global climate impotence on the part of leading nations.

Given such a grim reality, it’s hard to see how people can be seriously talking about a “good Anthropocene” with a straight face. When some climate scientists are caught in a more sober state of mind, the really honest ones will say that the 4-6-degree C scenario is far more likely by 2100, since every time the IPCC puts out a new report that main theme is ‘hey, you know that last report we put out? Well everything worse and happening faster than we thought back then’. To make matters worse, nobody on the techno-utopian side seems to even be willing to acknowledge these inconvenient truths, probably because there is no tech unfix for a cooked planet that resembles the Jurassic Era far more than anything we even knew from the Holocene Epoch, except for the higher Co2 and warmer global temperatures, which we are rapidly approaching. So while we march in the streets by the hundreds of thousands (300,000+ just here in NYC recently), the world leaders continue to twiddle their thumbs and point fingers.

With this kind of political reality, the last thing we need is yet another advocate for the “good Anthropocene”!

Until next time…remember, hope didn’t save the Dodo, and it won’t save us either.

###