Occupy Wall Street -vs- the State? Some Theoretical Reflections

The following musing was is attempt at a Comprehensive Exam response to a question regarding he role of the state in forming and influencing social movements. I figured I would post it so the time spent thinking would not be totally insular. I’d love to hear what you think? Footnotes are at the end of the piece.

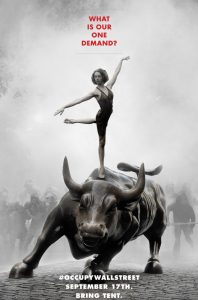

I believe a convincing argument could be made for the position that the state is the most important factor that shapes or influences popular social movements here and abroad. I also believe a convincing argument could be made for the position that the state is not the most important factor in shaping or influencing popular social movements here and abroad. In what follows, I consider various arguments for these two positions through the empirical lens of a contemporary social movement, Occupy Wall Street (OWS).1 I believe the emergence and trajectory of OWS here in the NYC offers an excellent lab (or case study, to use the comparative lingo) for us to think about the role of the state.

Let us begin by thinking about this question from a non state-centric position which argues that we should not a priori assume the state is the most important factor influencing popular movements. There are a number of factor, such as racial politics or corporate power, that could be the primary focus of a social movement. While this should is not an argument against the the state having any role—for example affirmative action policies are certainly bound up with the state—it could just as well be larger socioeconomic structures which we are the primary concerns or focus of a social movement. Therefore they might find their energy better spent in something like anti-racist organizing, rather than a direct engagement with state bureaucracy. One such example might include the free lunch program by the Black Panthers. Such a perspective still allows room to ascribe some level of importance regarding the interactions and influences of the state on these movements without needing to be rigidly state-centric.

The OWS protests provide another such example. Although state policies are certainly one influence on the movement (federal bailouts being an obvious example), attempts to capture or engage with the state machinery (as is typical of past social movements) is not a main focus of the movement—at least not on any meaningful scale. The primary interaction between OWS and the state so far has involved clashes with the NYPD. Rather than placing emphasis on the state, the OWS movement has focused more on socioeconomic concerns linked to economic elites (the 1%) and global capitalism. In this sense, OWS more closely resembles a social movement rather than an organization, an important distinction discussed by Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward in their work on social movements.

Furthermore, our emphasis is on collective defiance as the key and distinguishing features of a protest movement, but defiance tends to be omitted or understood in standard definitions simply because defiance dose not usually characterize the activities of formal organizations that arise on the crest of protest movements…the effect of equating movements with movement organizations—and thus requiring that protests have a leader, a constitution, a legislative program, or at least a banner before they are recognized as such—is to divert attention from many forms of political unrest…2

Because of the mix of anti-state and radical egalitarian influences within the movement, there has been a remarkable level of horizontal organizing not focused on the state, especially given the growing size and connections with more institutionalized social protest movement, such as organized labor and NGOs. What Adam Przeworski’s terms opposition radicals still have the most visible influence on the social movements in the streets at the moment, even though a growing number of reform groups are beginning to join the occupation.3 How this will play out remains to be seen, but for the moment the more militant direction appears to be emanating largely from student leadership.

A second related view might consider this question from a neutral position which argues the state is losing legitimacy due to failures of liberalization or some other de-democratization process (i.e. corruption), and thus its influence on social movements is also declining. So rather than arguing against the state as a central determinant on philosophical ground, it would argue more from a practical base. Here we might examine the OWS movement in relation to existing social movement NGOs that appear more in line with something like Przeworski’s description of the moderate opposition in his four-fold typology of political transitions. So far the movement has resisted moderate political co-optation, but as the movement grows, wider social instability may draw in more moderate and entrenched interest and with them new pressures to negotiate and compromise with existing state forms of power.

While the U.S. is not at a moment where cravat wearing gentlemen negotiating revolutionary demands in palaces as discussed by Przeworski, growing social disruptions could force institutional reformists to pick sides in order to counter consolidation efforts by hardline elements in the regime.4 For example, House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi offers a possible example of a reformer response: “I support the message to the establishment, whether it’s Wall Street or the political establishment and the rest, that change has to happen…People are angry.”5 Conversely, Republican Presidential candidate Herman Cain has advanced a hardline position in response to growing social disruptions and protests:

We know that the unions and certain union related organizations have been behind these protests that are going on on Wall Street and other parts around the country. It’s coordinated to create a distraction so people won’t focus on the failed policies of this administration.

It’s anti-American because to protest Wall Street and the bankers is basically saying that you’re anti-capitalism. The free market system and capitalism are the two things that have allowed this nation and this economy to become the biggest in the world.6

Here we can see a demonstration of what Piven and Cloward describe as elite tactics to marginalize or demonize popular social movements. For Piven and Cloward, power is “rooted in the control of coercive force and in the control of the means of production,” but in capitalist societies like the United States, “this reality is not legitimated by rendering the powerful divine, but by obscuring their existence.”7 This view is also shared by many currently protesting in the streets of New York. We should also note that Cain’s comments concerning the protests on Wall Street, that they are designed to “create a distraction so people won’t focus on the failed policies of this administration” is a perfect example of the process of elite misdirection described by the two authors, as is the tactic of switching between calling the protests a distraction and calling them anti-American for critiquing capitalism.

Critiques such as the one offered by Cain also reflect the problem institutional actors are facing when they try to engage with the OWS movement, in particular their frustration and inability to find suitable negotiating partners who would normally become the primary vehicle for co-optation of the movement by the state. McAdam, McCarthy and Zald make a similar point in their discussions of how states normally respond to social movements of this sort. “In the modern era, the demands of most movements are ultimately adjudicated by representatives of the state. To respond to a movement, state actors must focus on those movement leaders and organizations that seem to speak for the movement and yet who are perceived to be reliable negotiating partners.”8 Part of what I believe makes the OWS movement unlike past social movements in the U.S. is the lack of clearly identifiable movement leaders or visible NGOs who provide clear power brokers that can be co-opted into reformist state politics. Regime actors are unable to conceive of something like the General Assembly (GA) as a legitimate negotiating party, and the nature of Working Groups do not allow for negotiations on behalf of the larger GA. The same goes for the lack of any central party organ which could be negotiated with.

In this sense, what McAdam, McCarthy and Zald describe as the “radical flank effect” needs reformulating in this context, as OWS as a whole currently acts as a radical flank, rather than their being a radical flank with the larger OWS, as their model posits.9 In response to this dynamics, hardline opponents and their media proxies have attempted to discredit the movement by claiming they are largely made up of lazy and uninformed anti-capitalist, or that they are secretly funded and controlled by unions and liberal groups like MoveOn.org, AdBusters or the George Soros Foundation.10 Here I would disagree with McAdam, McCarthy and Zald’s argument that “just as the structure of political opportunities comes, in part, to be responsive to SMO [social movement organization] actions, so do later framing efforts come to be the product of formal organizational processes.”11 This claim falls within my general critique that elite bias argument are overly determinative in most comparative political work. This concern is also noted by Piven and Cloward in their study of popular social movements, where they argue that “whatever influence lower-class groups occasionally exert in American politics does not result from organization, but from mass protest and the disruptive consequence of protest.”12 It is still too early to speculate whether OWS will begin to be overtaken by larger and older social movement NGOs, but we should not preclude other potential trajectories.

One key aspects of the OWS movement is precisely that usual arguments about how traditional framing processes occur—that they tend to be “the exclusive ‘property’ of formal SMOs”—do not hold. I believe this is partly due to the anti-state undertone noted earlier in the movement, which is just as skeptical of formal SMOs as they are of the institutional political actors. I suspect it is also a function of the way that new social media platforms are operating, creating a dispersed, user-generated web of information networks, rather than one media source which can be controlled and centralized by a single group. These trends may also help to explain why the labor movement has been subordinated to more radical and horizontal leadership models through the General Assembly.

But what about more clear influences of the state, which is the flip side of our social movement discussion? In Adam Przeworski’s work on third wave democratization and regime transitions, he argues that a moderate opposition and an institutional reformer might agree on institutional changes more out of fear that the radical or hardline positions could use the crisis to either consolidate power or further disrupt the existing political order. This often leads to splinters within opposition groups, and those coalition re-alignments that create new political opportunities. As he suggests, “the struggle for democracy always takes place on two fronts: against the authoritarian regime for democracy and against one’s allies for the best place under democracy.”13 These new dynamics in turn leads to more social fracturing as old political alliances are broken and new ones are forged. Piven and Cloward’s prognosis on this dynamic in their discussion of popular social movements is worth recalling.

At times of rapid economic and social change, political leaders are far less free either to ignore disturbances or to employ punitive measures. At such times, the relationship of political leaders to their constituents is likely to become uncertain. This unsettled state of political affairs makes the regime far more sensitive to disturbances, for it is not only more likely that previously uninvolved groups will be activated—the scope of conflict will be widened, in Schattschneider’s terminology—but that the scope of conflict will be widened at a time when political alignments have already become unpredictable.14

It certainly appears that many of the underlying social issues which the OWS movement seeks to address, such as economic inequality, are likely to continue to widen into the foreseeable future.

At this point I want to pause and raise a potential difficulty with the analysis I have put forward so far. In most of the literature on democratization, and in much of the older social movement literature, the role of the state is more or less taken as a given. For example, Linz and Stepan describe the threshold for a successful democratic consolidation as when “democracy has become ‘the only game in town’.”15 The problem with such literature, and perhaps with the larger intersection of social movements and democratic theory in comparative politics in general, is how we go about theorizing democratization movements within already established democracies, in particular when the central critique of a social movement is precisely that a particular state claims to be democratic when in fact it is not. So for example, many of the categories used by Przeworksi, Huntington, Linz and Stepan and others focus on authoritarian or non-democratic regimes which are attempting to transition into some form of democratic or polyarchic institutions. How do we make sense of this literature when much of it already takes as a given that a country like the US is at the pinnacle of democratic consolidation, and measures democratization efforts against this assumed superior model? Do Przeworski’s hardline institutional players or moderate opposition groups still make sense if we try to apply them outside of a regime transition framework that does not start with an authoritarian state as the baseline?

I ask this because in some ways Przeworski’s analysis might be useful as an explanation for some of what is happening in this country, and perhaps also on the larger international stage. Reactionary and hardline political operatives have the Tea Party and ultra-conservative party operatives like Herman Cain and Michelle Bachmann. But there are no institutionalized leftists who can serve as negotiators between OWS and the state, thus making for a messier fit with his model. This is partly the case because institutional reformers who, at least according to his model, should be able to forge alliances with opposition moderates, simply do not have any political leverage with the OWS movement. As Sidney Tarrow suggests in regard to political struggles, collective social action “becomes contentious when it is used by people who lack regular access to institutions, who act in the name of new or unaccepted claims, and who behave in ways that fundamentally challenge others or authorities.”16

What if the real challenge posed by OWS is their claim that the democratic state itself is the crisis. As comparative theorists interested in understanding the relation between the state and social movements today, we need to understand these responses as challenges which go beyond the state and point instead to global economic structures and multinational finance companies as more important influences on social movement trajectories. It’s no accident that the recent Oct. 15th Global Day of Action targeted CitiBank and Chase, rather than City Hall.

I would further argue that these same globalizing trends are also producing transnational social movements which are global in nature precisely because contemporary political problems can’t be solved by domestic policies. Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink make a similar argument when they claim activists networks “reach beyond policy change to advocate and instigate changes in the institutional and principled basis of international interactions.”17 This is certainly true of the latest wave of student-led occupations spanning from Chile to Italy and England to New York.

It is no accident that the “we are the 99%” meme has such a strong resonance with the public, as it taps into both the information and symbolic level of political influence as discussed by Keck and Sikkink.18 The information aspect is clear in most Occupy Wall Street materials discussing the class dynamics of the wealthy 1%, and even shows up in critical responses to the protests. “This is the natural product of Obama’s class warfare,” suggested Newt Gingrich during his appearance on Face the Nation.19 The fact that the language of class warfare is re-appearing in mainstream discourse is a sign of the symbolic influence these social movements are having on the public framing, or what Keck and Sikkink, borrowing from David Snow, refer to as frame alignment and frame resonance—the “ability to influence broader public understandings” towards accepting a particular political message.20

While there is no doubt that the role of the state is important, emerging trends in social movements are, I believe, calling into question some scholarship on social movements which suggests that the state must be the central focus. As I have tried to show, the OWS social movement is calling into question the role and necessity of the state as the main political agent, while at the same time it is constructing alternative institutions outside of existing state frameworks—a trend most visible in the creation of physical occupation site as liberated public spaces for popular gathering and assembly. How these movements relate to the state vary, both across cities and within countries, but they all have one thing in common, which is a belief that the old way of doing politics has failed, and that the real power today is no longer the state, but rather the corporation. Comparative theorists would do well to take note, as this may very well be the beginning of a new trend in social movement organizing.

1) Hereafter referred to as OWS.

2) Piven and Cloward. (1979). pg. 5.

3) Przeworski (1992). pg. 67.

4) Przeworski (1992). pg. 69.

5) http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/pelosi-supports-occupy-wall-street-movement/story?id=14696893

6) http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2011/10/02/ftn/main20117827.shtml

7) Piven and Cloward (1979). pg. 2

8) McAdam, McCarthy and Zald (1996). pg. 14.

9) In fairness to McAdams, McCarthy and Zald, it is worth pointing out that there are certainly elements within the larger OWS movement that are pushing for more militant confrontations—such as the student-led bank actions on Oct. 15th—but this has not led to any meaningful splits within the larger OWS movement at this point over tactics.

10) http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/10/14/us-wallstreet-protests-origins-idUSTRE79C1YN20111014

11) McAdam, McCarthy and Zald (1996). pg. 16.

12) Piven and Cloward (1979). pg. 36.

13) Przeworski (1992). pg. 67.

14) Piven and Cloward (1979). pg. 28.

15) Linz and Stepan (1996). pg. 5.

16) Tarrow (1998). pg. 3.

17) Keck and Sikkink (1998). pg. 2.

18) Keck and Sikkink (1998). pg. 16.

19) http://www.cbsnews.com/2102-3460_162-20117827.html

20) Keck and Sikkink (1998). pg. 17.

Bibliography

ABC News. “Pelosi Supports Occupy Wall Street Movement.” Oct. 9, 2011. <http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/pelosi-supports-occupy-wall-street-movement/story?id=14696893>

CBS News. “Face the Nation Transcripts”. Oct. 9, 2011. <http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2011/10/02/ftn/main20117827.shtml>.

Keck, Margaret and Kathryn Sikkink. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks In International Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1998.

Mason, Paul. “’Occupy’ is a response to economic permafrost.” BBC NewsNight. Oct. 16, 2011. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-15326636>.

McAdam, Doug, John McCarthy and Mayer Zald. Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements. London: Cambridge University Press. 1996.

Piven, Frances Fox and Richard Cloward. Poor People’s Movements: How They Succeed, Why They Fail. New York: Vintage Books. 1979.

Przeworski, Adam. “Transitions to Democracy” in Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1992.

Reuters. “Whose Behind the Wall Street Protests?” Oct. 13, 2011. <http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/10/14/us-wallstreet-protests-origins-idUSTRE79C1YN20111014>.

Tarrow, Sidney. Power in Movements: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. London: Cambridge University Press. 1998.

###